Redistricting

Redistricting

Redistricting, or community districting, is the process of creating representational district maps for states and local communities. By determining which neighborhoods are included in each mapped boundary, redistricting impacts how our communities are represented in the US and local government and determines how resources are distributed.

How Does Redistricting Work?

The Census and Apportionment

Every ten years, the US Census Bureau counts the United States population and uses the updated counts to determine which state populations have increased or decreased.

These new population counts are used to decide the number of representatives that each state in the country receives. By federal law, the size of the House of Representatives is set at 435 seats, but the number of elected representatives and their district areas change over time. This process is known as apportionment.

- Example: Based on the data released in the 2020 census, Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon’s populations grew, so they each gained a district and, therefore, one Congressional representative. Texas gained two districts and two representatives.

It’s crucial that the Census Bureau has sufficient time to carefully collect and review their data. Otherwise, we risk undercounting the population. The more complete the population count, the more likely districts will reflect our communities.

Redistricting Files

Following apportionment, more detailed information is released to each state (plus DC and Puerto Rico) in the form of “redistricting files.” This information includes details like race, voting age, and more. Once it is released, states can begin the redistricting process.

Drawing Our Communities

There is no universal process for drawing district maps, so states use different methods. These include:

-

Redistricting commissions: 17 states currently give some form of redistricting commission responsibility over the map-drawing process. The commission may be made up of voters residing in the state (independent commissions), voters and representatives from both parties (bipartisan commissions), legislators (advisory commissions), or a backup group if the primary commission is unable to create new maps (backup commissions).

-

State legislators: 33 states currently assign redistricting to their legislators. Unfortunately, with legislators drawing their own boundaries, there is ample room for political bias and gerrymandering.

The Threat of Gerrymandering

Historically, politicians have manipulated the redistricting process to expand or protect their own power—often to the detriment of the minority political party, marginalized populations, and often, Black communities. This manipulation is called gerrymandering.

There are two primary methods of gerrymandering:

Racial Gerrymandering:

When mapmakers draw boundaries to either benefit or disenfranchise members of a certain race.

Example:

In 2016, the Republican majority redrew the North Carolina legislative districts after the US Supreme Court deemed the 2011 maps unlawful. When redrawing the maps, the largest historically Black college in the country, North Carolina A&T State University, was split into two different districts. As student Love Caesar noted at the time, “This many students have the ability to sway any election. Dividing that in half, putting half this way, half the other in a majority-Republican district, that definitely dilutes the vote.” This is a gerrymander that targets the political power of a racial group for the benefit of the political party in power.

Political Gerrymandering

When maps are drawn to increase or decrease the influence of a particular political party.

Example:

In 2016, Maryland elected Democrats to seven of their eight Congressional seats, despite the fact that Democrats earned roughly 60% of the popular vote. While the Supreme Court failed to find that partisan politics played too strong of a role, many people believe this was a clear case of partisan gerrymandering.

In 2019, the Maryland case (see above, political gerrymandering) was heard by the Supreme Court alongside the League’s case Rucho v. League of Women Voters of North Carolina. These cases argued that the political parties in power drew electoral district lines in a way that discriminated against their opposing political parties. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court ruled that there is no fair way to determine whether gerrymandering has gone too far in any state. As a result, federal courts will be hands-off in the redistricting process even when new district lines are drawn to intentionally decrease people’s voting power based on their political party.

We continue to fight racial and partisan gerrymandering and advocate for a fair and transparent process that produces the most representative maps.

Support the fight for everyone's freedom to vote.

How We Fight For Fair Redistricting Maps

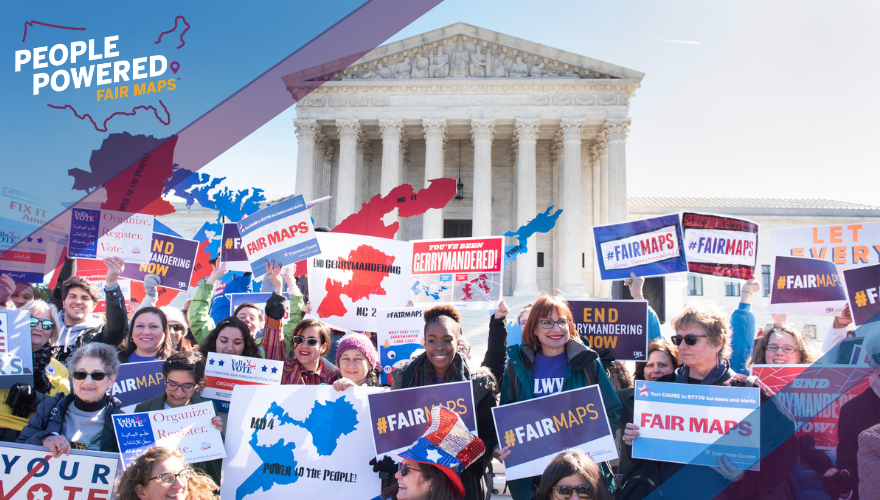

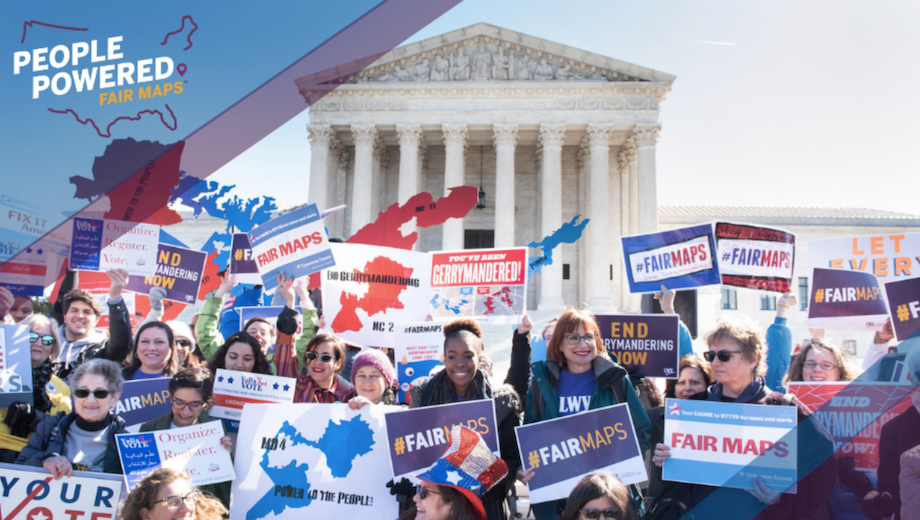

People Powered Fair Maps™

In 2019, we launched the People Powered Fair Maps™ (PPFM) program to advocate for the creation of equitable, accurate maps in all 50 states and DC and to educate about redistricting and increase public engagement in the 2021 map drawing process.

People Powered Fair Maps™ focuses on:

- Ensuring equity and transparency in the map-drawing process

- Advocating for independent redistricting commissions and the integrity of existing commissions

- Pushing for restoration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Monitoring and protecting the “free and fair” clause in state constitutions

- Increasing education and public engagement in the community districting process

New Laws For Fair Redistricting

There are efforts at the state and federal level to create a fair and consistent redistricting process nationwide. We support legislation that would restore the Voting Rights Act to its full power.

Take Action

- Follow the People Powered Fair Maps™ program on OutreachCircle to stay up to date on ways to remain engaged on a national and local activities.

- Spread the word about redistricting to friends and family by sharing the page on social media.

Join Your Local League

Connect with your local League of Women Voters and learn how you participate in the map drawing process.

LWV of South Carolina and LWVUS filed amicus briefs supporting plaintiffs seeking to uphold a district court ruling finding a racially gerrymandered congressional district in South Carolina

Plaintiffs sued in federal court to require Alabama to draw a second majority-Black Congressional district under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

LWV Indiana and its co-plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against the Anderson, Indiana, city council asserting its failure to redistrict city council districts violated state and federal law

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate and support our work

to build equitable community district maps and end gerrymandering.

_5.png)